12

-

- When you have studied this material, you should:

● understand energy audits in industrial facilities

● preparing for the audit

● a step-by-step guide to the audit methodology

● establish the audit mandate

● analyse energy consumption and costs

● Comparitive analysis

● Profile energy use patterns

● Assess the costs and benefits - When you have studied this material, you should:

-

- what is an energy audit?

- An energy audit is key to developing an energy management program. Although energy audits have various degrees of complexity and can vary widely from one organization to another, every audit typically involves

■ data collection and review

■ plant surveys and system measurements

■ observation and review of operating practices

■ data analysis

In short, the audit is designed to determine where, when, why and how energy is being used. This information can then be used to identify opportunities to improve efficiency, decrease energy costs and reduce greenhouse gas emissions that contribute to climate change. Energy audits can also verify the effectiveness of energy management opportunities (EMOs) after they have been implemented.

Although energy audits are often carried out by external consultants, there is a great deal that can be done using internal resources. This guide, which has been developed by Natural Resources Canada, presents a practical, user-friendly method of undertaking energy audits in industrial facilities so that even small enterprises can incorporate auditing into their overall energy management strategies. -

- In-House Energy Audit

- Consider the following simple definition of an energy audit:

“An energy audit is developing an understanding of the specific energy-using patterns of a particular facility.” – Carl E. Salas, p.eng.

Note that this definition does not specifically refer to energy-saving measures. It does, however, suggest that understanding how a facility uses energy leads to identifying ways to reduce that energy consumption.

Audits performed externally tend to focus on energy-saving technologies and capital improvements. Audits conducted in-house tend to reveal energy-saving opportunities that are less capital intensive and focus more on operations. Organizations that conduct an energy audit internally gain considerable experience in how to manage their energy consumption and costs. By going through the auditing process, employees come to regard energy as a manageable expense, are able to analyse critically the way their facility uses energy, and are more aware of how their day-to-day actions affect plant energy consumption.

By conducting an in-house audit before enlisting outside experts, organizations will become more “energy aware” and be able to address energy-saving opportunities that are readily apparent, especially those that require no extensive engineering analysis. External experts can then focus on potential energy savings that are more complex. The in-house audit can narrow the focus of external auditors to those systems that are particularly energy intensive or complex. -

- Systems Approach to Energy Auditing

- Structure of an Energy-Consuming System

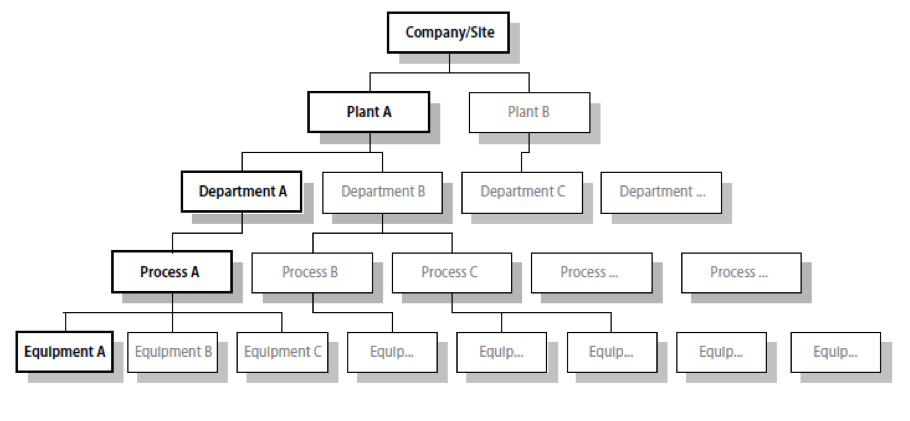

An energy-consuming system is a collection of components that consume energy. Energy audits can examine systems that may be as extensive as a multi-plant and multi-process industrial site or as limited as a single piece of equipment, such as a boiler. Figure 1.1 illustrates the generic structure of an energy-consuming system at an industrial site.

For simplicity, Figure 1.1 shows only one branch for each subordinate level in the system hierarchy. Real systems have many branches from each component to various lower levels. The concept of an energy-consuming system can be applied to a site, plant, department, process or piece of equipment, or any combination of these.

12.3.2 Structure of an Energy-Consuming System

The challenge of an energy audit is to

● define the system being considered

● measure energy flows into and out of the system

The first of these challenges is to define a system’s boundary. As already noted, by “system” we mean any energy-consuming building, area within a building, operating system, collection of pieces of equipment or individual piece of equipment. Around these elements we can place a figurative boundary. In a schematic diagram (Figure 1.1), a line drawn around the chosen elements runs inward from the facility level to specific pieces of equipment.

The second challenge is more difficult technically because it involves collecting energy flow data from various sources through direct measurement. It also likely involves estimating energy flows that cannot be directly measured, such as heat loss through a wall or in vented air. Keeping in mind that the only energy flows of concern are those that cross the system boundary, consider the following when measuring energy flows:

● select convenient units of measurement that can be converted to one unit for consolidation of data (for example, express all measurements in equivalent kWh or MJ)

● know how to calculate the energy contained in material flows such as hot water to drain, cooled air to vent, intrinsic energy in processed materials, etc.

● know how to calculate heat from various precursor energy forms, -

- Defining the Energy Audit

- There is no single agreed-upon set of definitions for the various levels of energy audits. We have chosen the terms “macro-audit” and “micro-audit” to refer to the level of detail of an audit. Level of detail is the first significant characteristic of an audit. The second significant characteristic is the audit’s physical extent or scope. By this we mean the size of the system being audited in terms of the number of its subsystems and components.

The macro-audit starts at a relatively high level in the structure of energy-consuming systems – perhaps the entire site or facility – and addresses a particular level of information, or “macro-detail,” that allows EMOs to be identified. A macro-audit involves a broad physical scope and less detail.

The micro-audit, which has a narrower scope, often begins where the macro-audit ends and works through analysis to measure levels of greater detail. A micro-audit might be a production unit, energy-consuming system or individual piece of equipment. Generally, as an audit’s level of detail increases, its physical scope decreases. The opposite is also true: if the scope is increased, the level of detail of the analysis tends to drop.

The auditing method presented in this guide applies to both the macro- and the micro audit. Data collection and analysis steps should be followed as closely as it is possible and practical to do so, regardless of the audit’s scope or level of detail. When using in-house resources, organizations are more likely to carry out macro-audits than micro-audits. Micro-level analysis can require expertise in engineering and analysis that is beyond the scope of this guide. -

- A Practical Auditing Methodology

- The energy audit is a systematic assessment of current energy-use practices, from point of purchase to point of end-use. Just as a financial audit examines expenditures of money, the energy audit identifies how energy is handled and consumed, i.e. n how and where energy enters the facility, department, system or piece of equipment n where it goes and how it is used n any variances between inputs and uses n how it can be used more effectively or efficiently

The key steps in an energy audit are as follows:

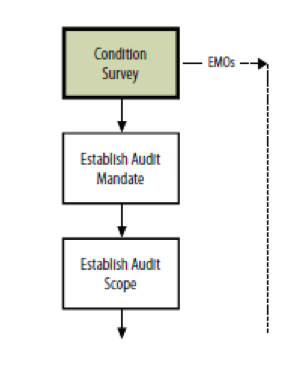

1. Conduct a condition survey – Assess the general level of repair, housekeeping and operational practices that have a bearing on energy efficiency and flag situations that warrant further assessment as the audit progresses.

2. Establish the audit mandate – Obtain commitment from management and define the expectations and outcomes of the audit.

3. Establish the audit scope – Define the energy-consuming system to be audited.

4. Analyse energy consumption and costs – Collect, organize, summarize and analyse historical energy billings and the tariffs that apply to them.

5. Compare energy performance – Determine energy use indices and compare them internally from one period to another, from one facility to a similar one within your organization, from one system to a similar one, or externally to best practices available within your industry.

6. Profile energy use patterns – Determine the time relationships of energy use, such as the electricity demand profile.

7. Inventory energy use – Prepare a list of all energyconsuming loads in the audit area and measure their consumption and demand characteristics.

8. Identify Energy Management Opportunities (EMOs) – Include operational and technological measures to reduce energy waste.

9. Assess the benefits – Measure potential energy and cost savings, along with any co-benefits.

10. Report for action – Report the audit findings and communicate them as needed for successful implementation.

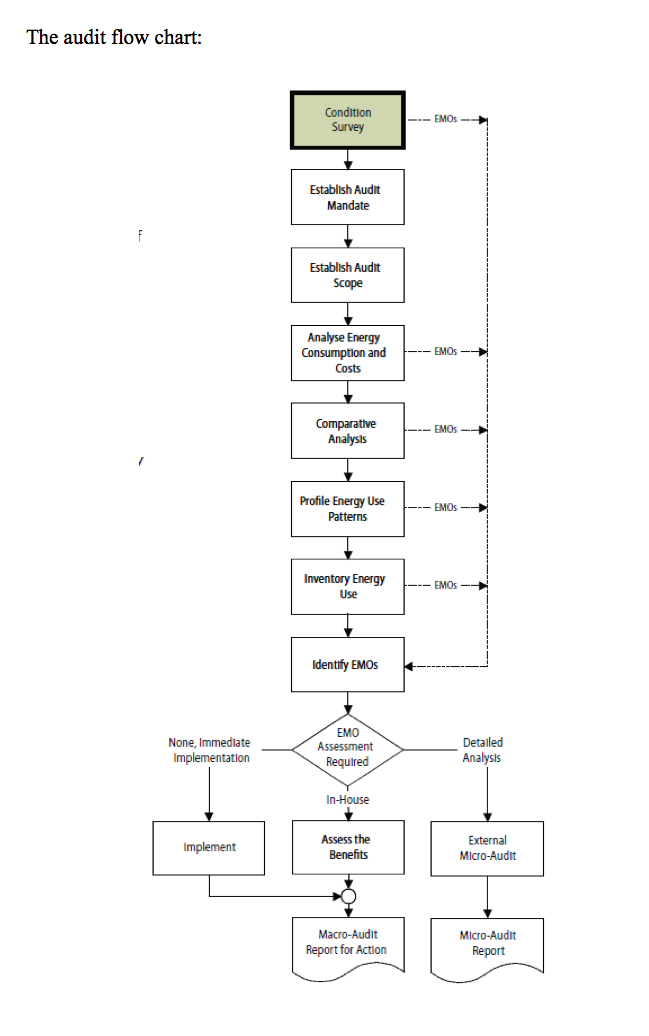

Each step involves a number of tasks that are described in the following sections. As illustrated in Figure 1.2, several of the steps may result in identifying potential EMOs. Some EMOs will be beyond the scope of a macro-audit, requiring a more detailed study by a consultant (i.e. an external micro-audit).

Other EMOs will not need further study because the expected savings will be significant and rapid; such EMOs should be acted on right away. -

- Preparing for the Audit

- Developing an Audit Plan

An audit plan is a “living” document that outlines the audit’s strategy and process.

Although it should be well defined, an audit plan must be flexible enough to accommodate adjustments to allow for unexpected information and/or changed conditions. An audit plan is also a vital communications tool for ensuring that the audit will be consistent, complete and effective in its use of resources.

Your audit plan should provide the following:

• the audit mandate and scope

• when and where the audit will be conducted

• details of the organizational and functional units to be audited (including contact information)

• elements of the audit that have a high priority

• the timetable for major audit activities

• names of audit team members

• the format of the audit report, what it will contain, and deadlines for completion and distribution

- Coordinating With Various Plant Departments

- Coordinating with production departments, engineering, plant operations and maintenance, etc. is critical to a successful audit. A good initial meeting with staff, representing all plant departments involved in the audit, can form a foundation for developing confidence in the process and, ultimately, the audit’s findings.

Consider the following when coordinating the audit with plant departments:

• review the audit purposes (objectives), scope and plan

• adjust the audit plan as required

• describe and ensure understanding of the audit methodologies

• define communications links during the audit

• confirm the availability of resources and facilities

• confirm the schedule of meetings (including the closing meeting) with the audit’s management group

• inform the audit team of pertinent health, safety and emergency procedures

• answer questions

• ensure that everyone is thoroughly familiar and comfortable with the audit’s purposes and outcomes

Another option is to create an audit team at the outset, not only to solicit input at the planning stages but also to garner support and resources throughout the audit.

Whatever method you use, assure all affected departments that they will be given the audit results and encourage their involvement in the audit process. -

- Defining Audit Resources

- You should decide early on whether to carry out the audit using in-house expertise or an outside consultant, as the auditor needs to be involved in the process right from the start. That person will drive work on determining the audit scope and criteria and other preparations. (Note: It is understood that the use of “auditor” in this guide can mean an entire team of auditors, as appropriate to the circumstances.)

Of course, the auditor must be a competent professional, one who is familiar with energy auditing process and techniques. When considering outside consultants, it pays to shop around and obtain references.

In order for the audit results to be credible, choose an auditor based on his or her independence and objectivity, both real and perceived. The ideal auditor will

• be independent of audited activities, both by organizational position and by personal goals

• be free of personal bias

• be known for high personal integrity and objectivity

• be known to apply due professional care in his or her work

The auditor’s conclusions should not be influenced by the audit’s possible impact on the business unit concerned or schedules of production. One way to ensure that the auditor is independent, unbiased and capable of bringing a fresh point of view is to use an independent consultant or internal staff from a different business unit. -

- The Condition Survey

- The Condition Survey – an initial walk-through of the facility – is essentially an inspection tour. Attention should be given to

• where energy is obviously being wasted

• where repair or maintenance work is needed

• where capital investment may be needed in order to improve energy efficiency

The Condition Survey has at least three purposes:

• It provides the auditor and/or audit team with an orientation of the entire facility to observe its major uses of energy and the factors that influence those uses.

• It helps to identify areas that warrant further examination for potential energy management opportunities (EMOs) before establishing the audit’s mandate and scope.

• It identifies obvious opportunities for energy savings that can be implemented with little or no further assessment. Often these are instances of poor repair or housekeeping that involve no significant capital expenditure.

- A Systematic Approach

- It is important for the Condition Survey to be comprehensive and systematic. Although the information obtained by the survey will be primarily qualitative, it can be useful to give a numerical score to each survey observation to help determine the scope and urgency of any corrective actions. Below is a checklist template for collecting information. It includes a point rating system. The checklist template can be readily modified and adapted to your facility; for example, in a survey of lighting, a line can be created for each room or distinct area in your facility.

- Finding Energy Management Opportunities (EMOs)

- Although the Condition Survey precedes the main audit, it can also identify EMOs. The survey rating system helps to identify and prioritize areas of the facility that should be assessed more extensively. However, direct observations of housekeeping, maintenance and other procedures can lead to EMOs that need no further assessment and that can be acted on right away. For example, fixing leaks in the steam system, broken glazing and shipping dock

-

- Establish the Audit Mandate

- Introduction

It can be tempting to move quickly into the audit itself, especially for auditors who are technically oriented. However, knowing the “ground rules” in advance will help auditors to use their time to maximum effect and will ensure that the needs of the organization commissioning the audit are met.

The terms of reference presented to the energy auditor are as follows:

• audit mandate – this should make the audit’s goals and objectives clear and outline the key constraints that will apply when the audit’s recommendations are implemented • audit scope – the physical extent of the audit’s focus should be specified, and the kinds of information and analytical approaches that will comprise the auditor’s work should be identified

The following checklist can help articulate a clear and concise audit mandate. A similar approach to defining the audit’s scope follows in Section 3.

- Audit Mandate Checklist 📷

- Define the System to Be Audited

This step defines the audit’s boundaries and the specifics of the energy systems within those boundaries. Although details on the energy load inventory will emerge from the audit process itself, it is useful to define the areas to be examined, as outlined in the Audit Scope Checklist .

Identify Energy Inputs and Outputs

Using a schematic diagram of the area being audited, you should be able to list energy inputs and outputs. It is important to identify all flows, whether they are intended (directly measurable) or unintended (not directly measurable). Obvious energy flows are electricity, fuel, steam and other direct energy inputs; and flue gas, water to drain, vented air and other apparent outputs. Less obvious energy flows may be heat loss though the building envelope or the intrinsic energy in produced goods.

Identify Subsystems Each of the systems to be considered in the audit should be identified, as outlined in the Audit Scope Checklist below.

- Audit Scope Checklist 📷

- Sample Energy Audit Scope of Work

1 Historical Cost and Consumption Analysis

1.1 Regression analysis of gas versus weather and production

1.2 Regression of electricity versus production

1.3 Summary breakdown of energy use from historical data

2 Electrical Comparative Analysis

2.1 Electrical energy versus weights by batch data analysis

2.1.1 Monthly historical – from existing data

2.1.2 By batch for audit test period

2.2 Estimate potential savings from ongoing monitoring

2.3 Prepare spreadsheet for ongoing analysis

3 Natural Gas Comparative Analysis

3.1 Gas energy versus batch weights analysis

3.1.1 Monthly historical – by oven, by product

3.1.2 By batch for audit test period – by oven, by product

3.2 Estimate potential savings from ongoing monitoring

4 Oven Preheat

4.1 Combustion testing (existing gas pressure)

4.2 Energy balance

4.3 Estimate savings for appropriate final temperatures

5 Air Exhaust/Make-up

5.1 Review air balance and determine energy and cost figures for estimated flows

5.2 Conduct combustion testing of unit heater under negative pressures

5.2.1 Estimate savings for operation at balanced pressures

5.3 Estimate savings for direct air make-up at workstations -

- Analyse Energy Consumption and Costs

- Introduction

Information in energy billings and cost records can lead to EMOs, especially when it is analysed with key energy use drivers such as production. You should analyse energy consumption and costs before comparing energy performance with internal and external benchmarks. Tabulating historical energy consumption records provides a summary of annual consumption at a glance. EMOs identified in this step may involve the reduction of energy consumption and/or cost, both of which are important outcomes.

Information in energy billings begins with the rate structures or tariffs under which energy is purchased. It is important for the auditor to understand the structure of tariffs and cost components fully because these will greatly influence savings calculations when EMOs are being assessed. Because the facility may use several energy sources, it is also important to understand the per-unit energy cost of these sources and their incremental cost (as opposed to just the average cost of energy).

In this section we outline the basic terminology involved in reading energy bills and show the reader how to tabulate billings in order to quantify past consumption levels and begin to identify consumption patterns.

- Purchased Energy Sources

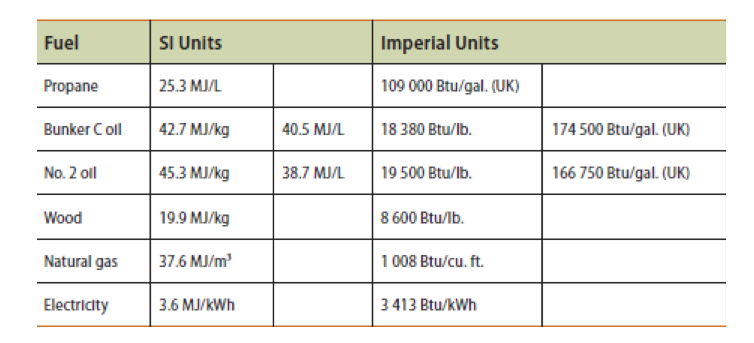

- Energy is purchased in a variety of commodities with varying energy content (see Table 4.1). This information is useful for analysing the unit cost of energy from various sources and making savings calculations.

Table 4.1 Energy Content of Various Fuels

-

- The Electricity Bill

- The information in an electricity bill includes the following:

• Kilowatt-hours (kWh) used: Energy consumed since the previous meter reading (also referred to as “consumption”).

• Metered demand (kW and/or kVA): Actual metered values of maximum demand recorded during the billing period. If both are provided, the power factor at the time of maximum demand can be calculated and may also be provided.

• Billing demand (kW and/or kVA): Demand value used to calculate the bill. It is the metered demand or some value calculated from the metered demand, depending on the utility rates.

• Rate code or tariff: Billing rate as applied to the energy and demand readings.

• Days: Number of days covered by the current bill. This is important to note because the time between readings can vary within ±5 days, making some monthly billed costs artificially higher or lower than others.

• Reading date: In the box called “Service To/From.” The “days used” and “reading date” can be used to correlate consumption or demand increases to production or weather - related factors.

• Load factor: Percent of energy consumed relative to the maximum energy that could have been consumed if the maximum demand had been constantly maintained throughout the billing period.

• Power factor: Ratio of recorded maximum kW to kVA (usually expressed as a decimal or percentage). -

- The Natural Gas Bill

- Gas companies use terms that can have different meanings within different rates. The following definitions are fairly standard. For specific terms and clauses, contact your gas utility representative, or refer to the latest rate tariffs for the appropriate rate and to the contract between your company and the utility.

• Days: Number of days covered by the current bill. This is important to note because the time between readings can vary anywhere within ± 5 days, making some monthly billed costs artificially higher or lower than others.

• Reading date: In the box called “Service To/From.” The “days used” and “reading date” can be used to correlate consumption or demand increases to production or weather factors.

• Contracted demand (CD): The pre-negotiated maximum daily usage, typically in m³/day.

• Overrun: The gas volume taken on any day in excess of the CD (e.g. 105%).

• Block rate: A rate where quantities of gas and/or CD are billed in preset groups. The first block is usually the most expensive; subsequent blocks are progressively less expensive.

• Customer charge: A fixed monthly service charge independent of any gas usage or CD.

• Demand charge: A fixed or block monthly charge based on the CD but independent of actual usage.

• Gas supply charge: The product charge (cents per m³) for gas purchased; commonly called the commodity charge. This is the competitive component of the natural gas bill. If you purchase gas from a supplier (not the gas utility to which you are connected), this charge will be set by that contract or supplier. The gas utility will also offer a default charge in this category.

• Delivery charge (re CD): A fixed or block monthly charge based on the CD but independent of actual usage.

• Delivery (commodity) charge (for gas delivered): The fixed or block delivery charge (cents per m³) for gas purchased. Overrun charge: Rate paid for all gas purchased as overrun. -